She rubs the lotion on her skin

/My dermatologist has a chart I can access at any time that shows me all the moles I should keep an eye on. It’s a three-dimensional model of a generic white woman wearing a ponytail, completely naked, not unlike myself every time I visit my doctor. She didn’t tell me about this chart, it wouldn’t interest most, but at times it gives me comfort. At other times, it becomes a laundry list of anxiety.

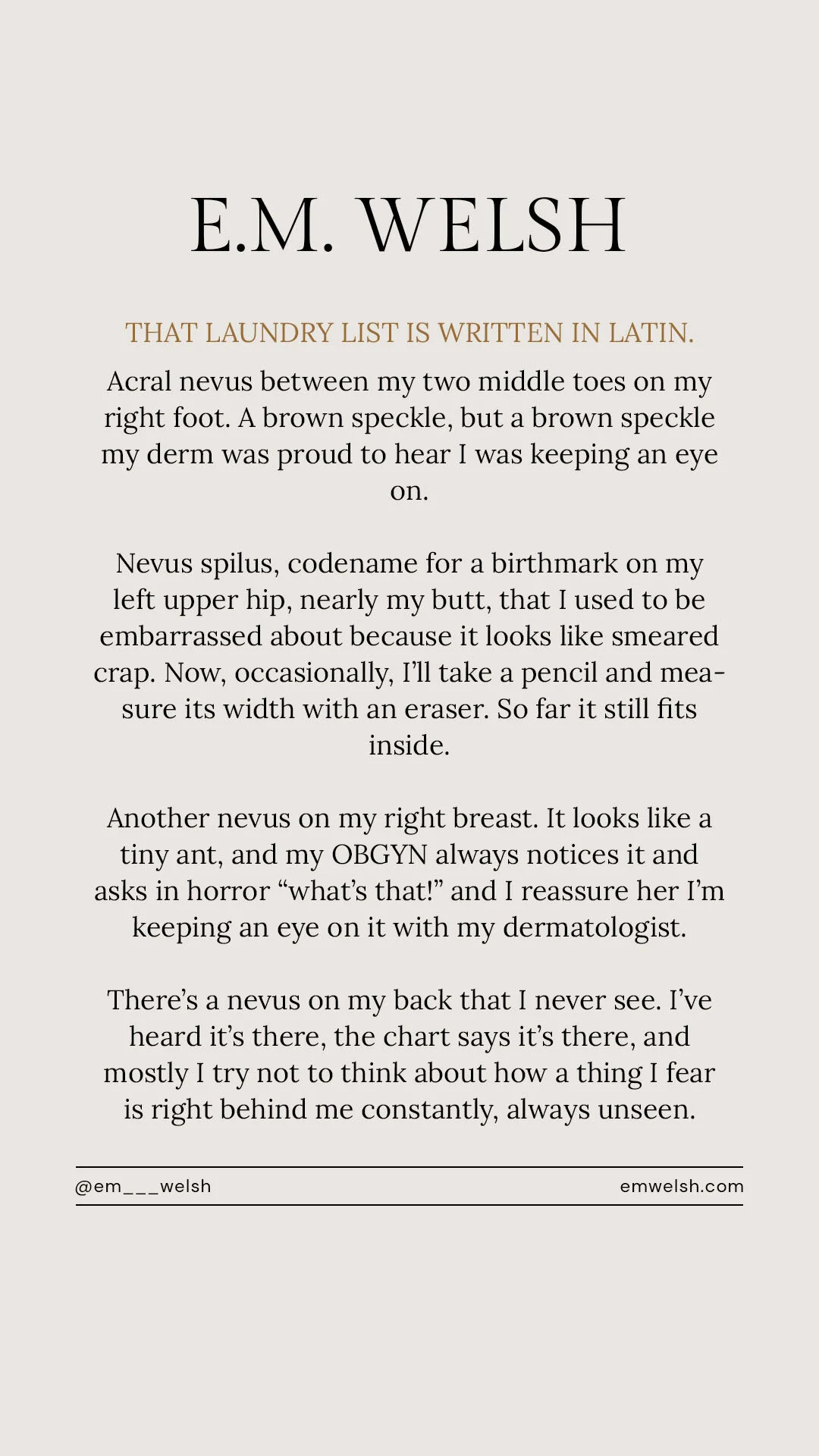

That laundry list is written in Latin.

Acral nevus between my two middle toes on my right foot. A brown speckle, but a brown speckle my derm was proud to hear I was keeping an eye on.

Nevus spilus, codename for a birthmark on my left upper hip, nearly my butt, that I used to be embarrassed about because it looks like smeared crap. Now, occasionally, I’ll take a pencil and measure its width with an eraser. So far it still fits inside.

Another nevus on my right breast. It looks like a tiny ant, and my OBGYN always notices it and asks in horror “what’s that!” and I reassure her I’m keeping an eye on it with my dermatologist.

There’s a nevus on my back that I never see. I’ve heard it’s there, the chart says it’s there, and mostly I try not to think about how a thing I fear is right behind me constantly, always unseen.

Blue nevus. It looks like a bowling ball, swirled, raised, outlined in brown on my left forearm. It’s terrifying, was the first reason I went to a dermatologist, and I stare at it constantly. With my first dermatologist, I begged him “Can you just remove it so I don’t have to look at it anymore?” He said sure, he’ll check with my insurance, that’ll be $250.

Then there’s recurrent nevus, the one that plagues me right now, and did the first time a year ago.

Before it was two small moles to me, side-by-side, compound nevus. I didn’t love them either, but they’d always been there. They were the first moles I knew I had. In seventh grade a guy in chemistry told me I had moles, pointing to the two brown moles nestled on top of one another. He was right. I did indeed have moles on me and not just freckles.

Another doctor told me to watch that same compound of blackish-brown cells—come to the doctor if it’s bigger than a pencil eraser. So I measured, and it never moved.

Covid delayed my yearly skin check up, and one evening I became certain the way I’m always “certain” a mole on my back had changed. I was running high on the anxiety we all were drowning in during early 2020, and my fears had found new form in my skin. But then, it wasn’t new at all. I’ve always had issues with my skin.

I had acne before anyone else my age. In second grade I learned what a cleanser was, and by fifth grade I was on topical acne cream. Seventh grade was Tazorac, a last-ditch effort before Accutane, and when the nurse practitioner gave me the cream she said “You’re going to have beautiful skin when you’re older.”

I didn’t really like hearing that as the lone middle-schooler in the office, arguably the only person under thirty.

First, I was slathering on acne medicine, a ritual I came to know for ten years. Then I moved on to Accutane and it was moisturizer, moisturizer, moisturizer. I carried Rosebud Salve in my pocket and country hicks asked if I was dipping. I went on it twice. It was never enough, there was always more acne. I had bet on getting acne early, then it stopping early. But instead, I got acne early and then everyone else joined the party, except my party involved monthly blood tests and abstinence quizzes.

It wasn’t until I was twenty-one, and Korean beauty took over the nation, that finally my battle with acne ended and people began to do the unheard of, which was compliment my skin. It was twelve steps for me of BHA, AHA, retinols, vitamin C, toner, snail mucin essence, green tea serum, sleeping masks, eye cream, sheet masks. And like a miracle, my acne went away, only for some new skin condition to join the ranks.

I was on a grassy hill in Madrid when my calves turned bright red from sitting in the grass. I didn’t think much about it until I came home to the U.S,. and I cleared my acne, but then my legs were itchy all—the—time.

Now I was putting lotion on my legs, on my arms, on my torso. My face was clear but my body was greasy from ointments and lotions. Sometimes I’d wear skirts so my legs could breathe, but I’d only end up scratching them so hard they would gush blood and I’d have to sleep with towels on my legs so I didn’t stain my sheets. If I wore jeans to stop the scratching, they’d burn more and I’d get home and rip off my pants, and it’d be the same story all over again, just less publicly available.

Some doctors said it was ringworm and others said it was allergies or eczema. At times it would slowly crawl from my legs all the way up to my torso and arms like a disease. Once again, I felt like one. I was reminded of an early dermatologist I visited, who looked at my preteen acne and kept saying “We’re going to get you cured.”

Is my skin always something to cure?

The day before my family flew out to Alaska to meet my brother after his bike ride across the country, my skin was burning and covered in an inexplicable rash. “It’s an August issue” I eventually decided, telling myself it’s just something I’d get used to every fall. But sometimes then it would show up in the spring or in the winter and I’d have to rationalize a new reason why sometimes my legs are on fire and nothing feels more orgasmic than scratching them till they’re chalky but not yet bleeding.

It’s still an issue, but compared to my current plague I would take probably-eczema and occasional acne over fears around the c-word (which really means more the “d-word”).

Every visit I try to convince my dermatologist I am not a freak. I just have medical anxiety around anything related to my skin. Every time.

I act calm, prepared. I ask well-informed questions, I point out moles I have been keeping track of, and assure her nothing has changed. (Has anything changed?) We talk about how my bi-yearly visits are more frequent as a proactive measure. My dad had basal cell carcinoma. I have more than 50 moles, and many of them have forms of “atypia”—meaning we watch them because they’re weird and non-uniform. I played tennis in the sun for over a decade. My tennis coach got melanoma on his ear. I’m skin type 2, which means I’m pale, but I sometimes can tan after a burn. Two burns I’ve had were so bad my skin bubbled and blistered. That’s another risk for melanoma, by the way.

My first biopsy will not be my last. I knew this before I ever had a biopsy. I would say to people in high school that if I got any cancer, it would be skin cancer as if I get to pick and choose life’s tolls. But because of that, I’ve always been prepared. I’m the girl with the reputation of chastising people for not wearing SPF every day, the one who has a mini sunscreen in her purse, the one who has eyeshadow with SPF in it.

But no many how many layers of Supergoop you layer on, it can’t prepare you for the sickening week of waiting for a biopsy result.

It happened very fast.

“I’ve had this mole for years, but if you want to remove it and test it, please do.” They said they could remove it right then. “Oh, right now?” I said shocked, flipped over naked, and then they jabbed a needle in my bicep, and then shaved off the compound nevus and swiped it into a test tube. “You should hear back in about seven business days.”

Then it happened very slowly.

When I sat around waiting for my results, all I could think about was how my little mole was now sliced off and sitting in some test tube in a lab, a little sliver of me preserved elsewhere. I felt lonely, thinking about that isolated part of me, in a cold, unfeeling lab, tucked away in the dark at night.

The procedure to remove the mole was laughably easy. Waiting a week for the biopsy results was excruciating. Sometimes I would burst into tears, other times I would ask my brother or my boyfriend or my dad, again, “Do you think it’s cancer?” and they would sigh and tell me no, it’s likely not, it’s likely precautionary.

Seven business days. I hear that phrase when I order packages, when I wait for my tax return, when I call for office hours. That phrase isn’t for biopsy results. It’s much more urgent. Why aren’t people working around the clock to tell me the worst? Why can they go home and sit with their families, while I sit with mine and hardly see them? I try to have dinner or swim in the pool on Memorial Day weekend, and it’s all through this haze of maybe-the-worst-is-already-here. Why do biopsy results get Memorial Day off in the first place? Every day I don’t know is a day I have cancer untreated. Cancer doesn’t get Memorial Day off.

And then, on a Wednesday, they call me and say “It’s benign.” I knew it was benign of course. I’ve had it my entire life; it’s never changed. My hands are shaking when I answer the phone, when I hear the best news all week. I’m embarrassed by all the “I-told-you-so’s” heading my way, the patronizing smiles of those who knew—rationally and logically and with the clarity an anxiety-induced lady lacks—that I would be okay the entire time.

But it’s not the first time I’ve heard these I-told-you-so’s either. It’s not the first time my health anxiety has cornered me with embarrassment post-episode.

In Marrakech, I got a black henna tattoo with friends, and when it accidentally stained my new kaftan I looked up how to remove the stain only to see to my horror that black henna isn’t natural, and causes deathly reactions. On the train back to Santander, my home during that Spanish summer, I begged a friend to use their phone so I could call my university health services to tell them I was dying. The lady on the phone said, “Have you ever had a panic attack before, ma’am?”

I spent the whole ride back after that rubbing smelly Argan oil over my arm, harassing the lady next to me with the odor, and I clogged the bathroom toilet on our train car. Nobody could use it, and I wasn’t going to volunteer my broken Spanish to explain why.

When I got home, my host mom, Luchy, consoled me about dying her hair with black henna, and Profesora Chiyo called me to tell me in Spanish that they use that same henna in Japan for hair. Later, my classmates asked me if I was okay. I had posted a manic cry for help in our Facebook group.

“Tuve un ataque de pánico. Estoy bien.”

That was when my panic began around my skin. It’s why as I type this my heart races, and every few seconds I check that recurrent nevus to see if anything has changed. (It hasn’t. The photo album I have on my phone will prove it, but what good is rationality over the dogged mind of someone triggered into their anxiety?)

“It’ll scar,” they said before they removed my mole as if offering one last chance to keep my skin polished and unblemished. I almost laughed. Remove it, get rid of it. I have scars all over me from acne, from scratching my legs, my arms, my torso. At least banish the one thing where a scar is a good sign, a signal of maybe-cancer long gone. The idea that anyone would second guess the decision for cosmetic reasons baffled me.

But then that scar came back, and now it’s a mole again. It’s not compound anymore, it's recurring. And once again, we’re watching it.

Skin is my issue. Other people are plagued with much worse. And yet my life’s issues and fears have manifested themselves in my largest organ available. There have always been creams to fix my problems—Retin-A, Differin, SPF 50, PA++++, topical steroids, Cortizone. But maybe it’s because it feels like skin issues are a symptom of something dubious lurking underneath, bubbling up on the surface only when things are at their absolute worst. Stress, after all, manifests itself with a large pustular pimple or scathing hot legs. Who is to say it couldn’t be something worse sounding the alarm beneath my cells?

Or maybe, just maybe, it’s a lot of freaking stress. At least for now.